Sam Thacker was my friend. At 22, she had already served a tour in Iraq and been discharged from the U.S. Army. A month before her 23rd birthday, Sam died in a car crash in North Philly. She was in a neighborhood where no one who is up to any kind of good goes. She sideswiped a parked car and, when the owner of the vehicle started to understandably scream at her, Sam took off, lost control, and slammed into a telephone pole. She was braindead, and her mother told her doctors to let her go the next day.

What was she doing in that neighborhood? Buying heroin, of course.

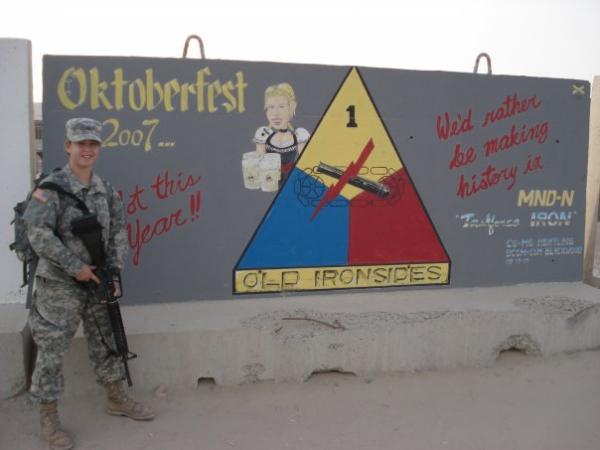

Sam saw a lot of bad things in Iraq. A lot of it she’d talk about — she had twelve confirmed kills, and she was proud of each one — and a lot of it she’d never broach. What haunted her the most, though, was her one fatal mistake. Sam, you see, worked in Army Intelligence as an interrogator, and had several informants throughout the region. During one particular night op, she fingered an individual for assassination. To her horror, she discovered far too late that the individual in question was one of her informants; an innocent man. She had, in her mind, murdered an innocent man.

The burden was too much for her. The confirmed kills, like I said, were a source of pride for her. They were The Enemy, they deserved it, and she had eliminated The Enemy. That was her job. But this guy did nothing wrong. This guy risked his life to bring her information. He didn’t deserve the fate that befell him.

Sam was discharged early for an unrelated injury (like so many of her peers, she was in a convoy that blew up). She had hoped that being home would help erase the ghost of this man, but it only made it worse. She sought help from the V.A., where she was diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. She spent a few stays in psychiatric facilities, but it didn’t help. The medicines didn’t help. Nothing helped, so Sam turned to heroin.

Here, in her mind, was salvation. She’d mainline, and as long as it was coursing through her system she didn’t think about Iraq. She didn’t think about the blood on her hands. She didn’t think about anything. I asked her once if she ever planned to stop taking it. Her reply was simple: “No. I’ll use this until I die.” Neither of us knew at the time that she’d be proven right a month later.

Sam’s story isn’t unique. We all know modern war veterans who served their time and came back… changed. I want to chronicle their stories.

I know very little about PTSD, other than the fact of its existence. I want to learn more about it, specifically in relation to how it affects veterans. What it does to them. How it’s treated. If that treatment is effective, and what the V.A. does when the treatment doesn’t work.

i want to understand what happened to my friend.

I know several vets who have been irrevocably changed by their time in Iraq and Afghanistan. They’ve never talked to me about what happened to them, and I’ve never asked, but I’ve seen the effects: inability to hold jobs, hiding under tables after loud noises, self-destructive behavior. I want to sit down with them and get them to open up. I want to know what they saw, what they heard, what they felt. I want to talk to their wives, their mothers and fathers, and find out what they’re like behind closed doors. What it’s like to live with someone who gave of themselves freely, and had so much taken from them.

I want to learn about the condition itself. I want to learn what causes it, neurologically. I want to know what treatments the V.A. tries to provide. I want to talk to the professionals who have worked with these soldiers, and I want to hear their stories, their triumphs and their failures.

And I want to know what more can be done. What average citizens can do. How we can help.

Theirs is a story that needs to be told. It’s a story that we all know of, but know very little about. I want my work to change that for everyone. I want to humanize these soldiers, and tell their story.

But how do I tell it? How do I grab audiences?

I thought of writing this up as a feature article when I’ve gotten far enough along in my research. A feature certainly has its attraction, but I’ve been writing journalistic pieces for half my life. I know their limitations; mainly, keeping the reader’s interest. Getting a reader to go below the fold or jump to the back of the publication is no easy task. If I want to grab them, hold them and keep them, and really move them, I’ve got to get creative; more creative than I’ve ever been before.

Marilyn Nelson, in A Wreath for Emmett Till, employs a heroic crown of sonnets with a Petrarchan rhyme scheme to tell the story of a young African-American boy who was lynched and hanged in the 1950s. The form is brilliant and the language – at times formal, at times conversationally grisly – is all the more powerful because of the structure.

It’s perfect for my purposes. It remains to be seen if I’ll follow in Ms. Nelson’s footsteps and employ a Petrarchan rhyme scheme, or if I’ll follow the more traditional Shakespearean route; or employ a combination of the two throughout the ensuing fifteen sonnets. I do know that the form I’m choosing is incredibly complicated but, if done correctly, is incredibly beautiful.

I’d love to see this published when I’m finished, but where? I could try to further follow in Nelson’s footsteps and approach Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; they do accept unagented submissions, so that’s certainly a consideration. Periodicals are also a way to go, but very few would tackle something of this length. Plus, how do I define it? As a heroic crown, where each sonnet is interlinked and is vital to the whole, is this, then, considered one poem in fifteen parts? Or would a periodical consider it fifteen separate poems?

Assuming that it’s one poem in fifteen parts, I’ve got a few options. The Malahat Review, out of Victoria, British Columbia, for example, accepts poems between 5-10 pages. Assuming they don’t give each sonnet its own page, this should certainly fit the parameters. I could also try Tampa Review. They’re taking all kinds of poetry, at a max of 225 lines. Fifteen sonnets at fourteen lines a piece – even accounting for spaces in between – comes in just under the mark, so they’re something to consider. Then there’s the North American Review, the oldest literary magazine in the country. They have no restrictions whatsoever on poetry, other than that it be of the “highest quality only.” I’ll have to revisit that idea when I actually have a finished product, and input from others before I assume that it’s “highest quality”.

If the project comes out as strong as I hope, I may submit it to the White Pine Press Poetry Prize contest. They take up to 80 pages, and the work could have previously appeared in a magazine. That’s something to hold on the back burner.

I’ve never attempted a project like this. The subject matter is largely foreign to me, and the form is way outside my comfort zone. But that’s fitting. What happened in Iraq was outside of Sam’s comfort zone, and she did it anyway. I’ve never served. I’ve never wanted to serve. But Sam did. And if going outside of my comfort zone gets her story told, and helps put human faces on PTSD, and helps even one vet, then that’s certainly the least that I can do.

Joe,

I am very sorry to read of Sam’s death. A terrible tragedy. So many veterans are impacted by these wars in ways that they seem not to have been in the past. The suicide rates are astronomical—and, I’m sure, the drug use.

This makes your topic all the more important. The main concern for me is whether your friends will be interested or willing to talk with you. If not, you may need to find another topic. I suspect you’ll know in a week or so if you’ll be able to talk with them. If you don’t think you will be able to, email me immediately so we can start locating a new topic.

Our readings on open interviewing will really help you so you’re able to focus on your role as listener and allow them the space to talk.

I also think the presentation as a group of sonnets is excellent, as it will bring you new writing challenges.

Looking forward to seeing how it goes!

BW

Interesting story. This makes me especially sad being a NJARNG soldier myself. Can’t wait to read the finished product.

Very powerful topic, Joe, and — of course — a well-written blog post. And a sonnet? You’re a better man than I, Gunga Din!

Joe,

For such a difficult topic, I think you write very clearly and the flow of your posts is great. I am so sorry to hear about your friend. I am looking forward to reading your blog and following your work. Good luck with your interviews. Can’t wait to read them.

Joe – sorry it took me so long to read your post. I think this is a great topic for a poetry piece. Have you written any poetry before? Prof. Block is a great resource who can help you with the technical challenges of the poem. Good luck! Can’t wait to read it!